Fermat's little theorem

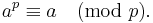

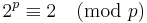

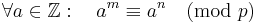

Fermat's little theorem (not to be confused with Fermat's last theorem) states that if p is a prime number, then for any integer a, a p − a will be evenly divisible by p. This can be expressed in the notation of modular arithmetic as follows:

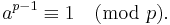

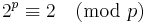

A variant of this theorem is stated in the following form: if p is a prime and a is an integer coprime to p, then a p−1 − 1 will be evenly divisible by p. In the notation of modular arithmetic:

Another way to state this is that if p is a prime number and a is any integer that does not have p as a factor, then a raised to the p − 1 power will leave a remainder of 1 when divided by p.

Fermat's little theorem is the basis for the Fermat primality test.

Contents |

History

Pierre de Fermat first stated the theorem in a letter dated October 18, 1640 to his friend and confidant Frénicle de Bessy as the following[1] : p divides a p−1 − 1 whenever p is prime and a is coprime to p.

As usual, Fermat did not prove his assertion, only stating:

Et cette proposition est généralement vraie en toutes progressions et en tous nombres premiers; de quoi je vous envoierois la démonstration, si je n'appréhendois d'être trop long.

(And this proposition is generally true for all progressions and for all prime numbers; the proof of which I would send to you, if I were not afraid to be too long.)

Euler first published a proof in 1736 in a paper entitled "Theorematum Quorundam ad Numeros Primos Spectantium Demonstratio", but Leibniz left virtually the same proof in an unpublished manuscript from sometime before 1683.

The term "Fermat's Little Theorem" was first used in 1913 in Zahlentheorie by Kurt Hensel:

Für jede endliche Gruppe besteht nun ein Fundamentalsatz, welcher der kleine Fermatsche Satz genannt zu werden pflegt, weil ein ganz spezieller Teil desselben zuerst von Fermat bewiesen worden ist."

(There is a fundamental theorem holding in every finite group, usually called Fermat's little Theorem because Fermat was the first to have proved a very special part of it.)

It was first used in English in an article by Irving Kaplansky, "Lucas's Tests for Mersenne Numbers," American Mathematical Monthly, 52 (Apr., 1945).

Further history

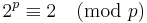

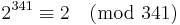

Chinese mathematicians independently made the related hypothesis (sometimes called the Chinese Hypothesis) that p is a prime if and only if  . It is true that if p is prime, then

. It is true that if p is prime, then  . This is a special case of Fermat's little theorem. However, the converse (if

. This is a special case of Fermat's little theorem. However, the converse (if  then p is prime) is false. Therefore, the hypothesis, as a whole, is false (for example,

then p is prime) is false. Therefore, the hypothesis, as a whole, is false (for example,  , but 341 = 11 × 31 is a pseudoprime. See below).

, but 341 = 11 × 31 is a pseudoprime. See below).

It is widely stated that the Chinese hypothesis was developed about 2000 years before Fermat's work in the 1600s. Despite the fact that the hypothesis is partially incorrect, it is noteworthy that it may have been known to ancient mathematicians. Some, however, claim that the widely propagated belief that the hypothesis was around so early sprouted from a misunderstanding, and that it was actually developed in 1872. For more on this, see (Ribenboim, 1995).

Proofs

Fermat gave his theorem without a proof. The first one who gave a proof was Gottfried Leibniz in a manuscript without a date, where he wrote also that he knew a proof before 1683.

Generalizations

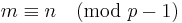

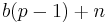

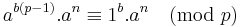

A slight generalization of the theorem, which immediately follows from it, is: if p is prime and m and n are positive integers such that

then

then  .

.

This follows as  is of the form

is of the form  , so

, so  .

.

In this form, the theorem is used to justify the RSA public key encryption method.

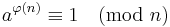

Fermat's little theorem is generalized by Euler's theorem: for any modulus n and any integer a coprime to n, we have

where φ(n) denotes Euler's totient function counting the integers between 1 and n that are coprime to n. This is indeed a generalization, because if n = p is a prime number, then φ(p) = p − 1.

This can be further generalized to Carmichael's theorem.

The theorem has a nice generalization also in finite fields.

Pseudoprimes

If a and p are coprime numbers such that a p−1 − 1 is divisible by p, then p need not be prime. If it is not, then p is called a pseudoprime to base a. F. Sarrus in 1820 found 341 = 11 × 31 as one of the first pseudoprimes, to base 2.

A number p that is a pseudoprime to base a for every number a coprime to p is called a Carmichael number (e.g. 561).

See also

- Fractions with prime denominators – numbers with behavior relating to Fermat's little theorem

- RSA – How Fermat's little theorem is essential to Internet security

- p-derivations

- Frobenius endomorphism

References

- Paulo Ribenboim (1995). The New Book of Prime Number Records (3rd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94457-5.

- János Bolyai and the pseudoprimes (in Hungarian)

External links

- Fermat's Little Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Euler Function and Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Fermat's Little Theorem and Sophie's Proof

- Text and translation of Fermat's letter to Frenicle

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Fermat's Little Theorem" from MathWorld.